We didn’t lose our inner child. We turned it into ArT Toys and More...with purpose.

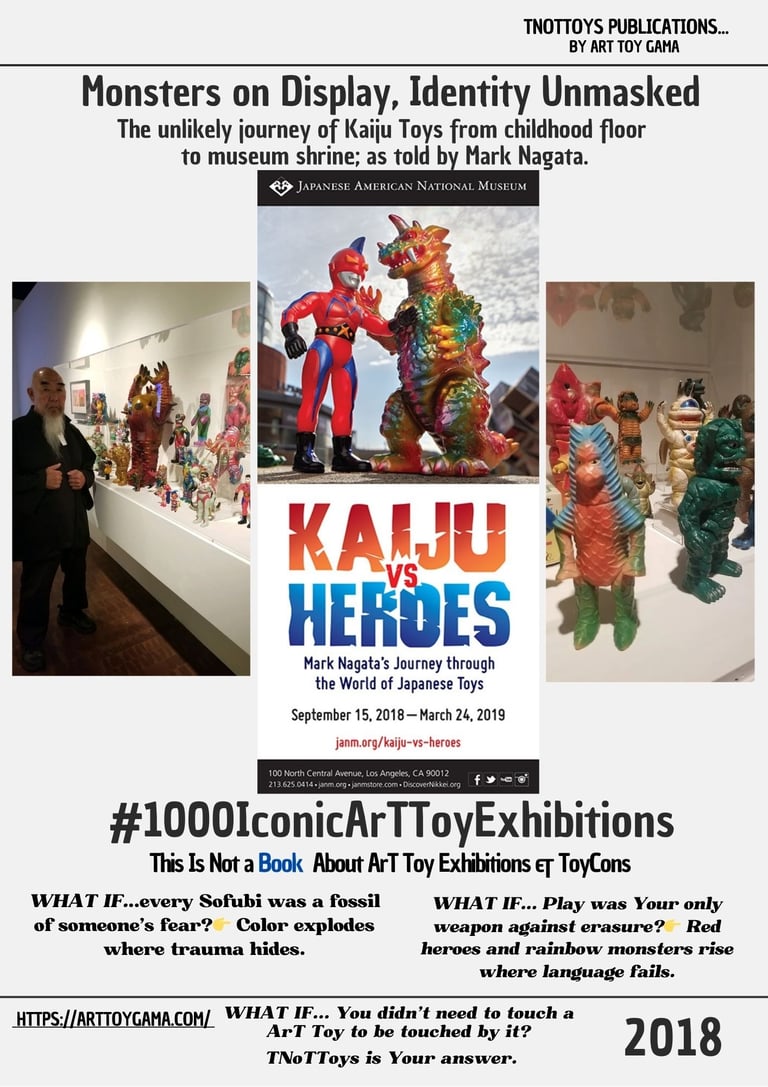

🕹️ Kaiju vs Heroes: When Collecting Becomes Identity

From childhood box to museum stage: how Mark Nagata turned Kaiju Toys into autobiography and legacy in 2018. Kaiju vs Heroes #00005 — TNoTToys Publications

TNOTTOYS PUBLICATIONS1000 ICONIC ART TOY EXHIBITIONSTNOTTOYS

Sergio Pampliega Campo & Cristina A. del Chicca

🌀 This post is part of an ongoing research series from Art Toy Gama’s editorial division:

📚 This Is Not a Book About Art Toy Exhibitions & ToyCons

Our Upcoming Art Toy Book: 1000 Iconic ArTToy Exhibitions

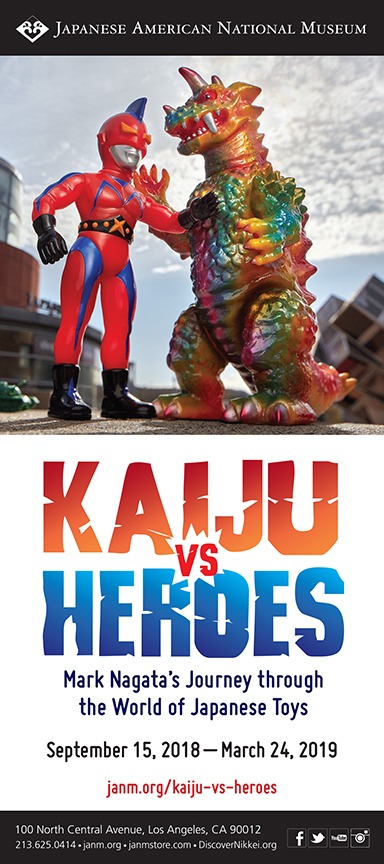

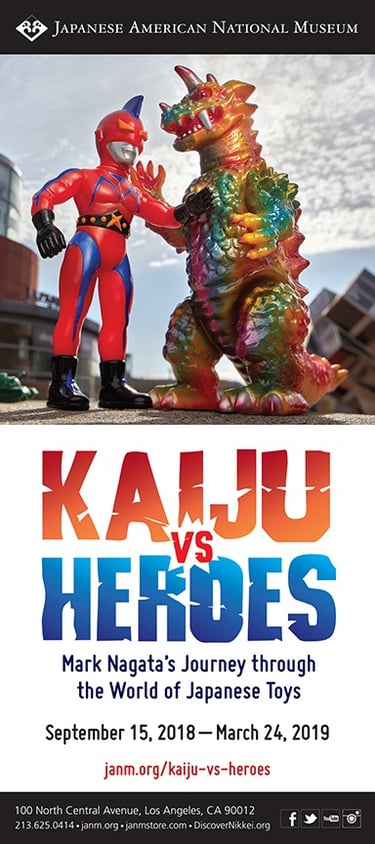

Los Angeles, 2018–2019 — JANM

Japanese American National Museum. Hundreds of vintage and contemporary sofubi. Paintings. Illustrations. Interactive experiences. And the life of a collector who became an artist: Kaiju vs Heroes: Mark Nagata’s Journey through the World of Japanese Toys.

The COVER image matters

The POSTER wasn’t just graphic design. It was declaration.

Captured by toy-photography pioneer Brian McCarty, the image stages two figures—Captain Maxx and Drazoran—that come straight from Mark Nagata’s imagination. They’re not anonymous kaiju; they are his own creations.

Fangs flash. Scales shimmer. A hero in red dives into chaos. At first, pulp spectacle. At second glance, autobiography. When the poster carries the artist’s characters, the POSTER itself becomes his memoir.

That’s why the museum didn’t treat it as disposable promo. It became an official print, sold alongside the show. Proof that here, even marketing turned into Memory.

✧ Extended POSTER Reading:

The Semiotic Duel Behind Kaiju vs Heroes

The POSTER doesn’t just stage two ArT Toys.

It stages a worldview.

It stages a biography.

It stages a cultural tension older than Nagata himself.

Look again.

1. The Visual Code: How the POSTER Behaves Like a Museum Label

The composition feels almost documentary.

Clear sky. Street-level angle. Urban sunlight hitting sofubi skin.

Not fantasy.

Not marketing gloss.

A field photograph.

This matters.

Because JANM is a museum of identity.

And the poster behaves like identity:

Direct. Present. Unmasked.

No explosions.

No special effects.

Just two figures standing in the world; claiming space.

Kaiju vs Heroes as self-portrait.

2. Typography as Lineage

The dual-color gradient in KAIJU and HEROES acts like a code.

Warm tones for monsters.

Cool tones for guardians.

A spectrum of conflict.

A tension in ink.

But the font is bold, blocky, almost American roadside signage.

Japanese Toys framed in Western typography.

Nagata’s life in one typographic gesture.

A hybrid identity printed in uppercase.

3. Composition as Myth-Building

The POSTER uses a low camera angle; classic tokusatsu language.

Heroes become monumental.

Monsters become topographical.

The city behind them shrinks.

Los Angeles becomes a model set.

Reality becomes stage.

Nagata is telling you:

“My ArT Toys are not small.

They are the architecture of the world I inhabit.”

4. The POSTER as Cultural Object

This Is Not a collector POSTER .

It is a cultural marker.

Placed inside JANM, a museum dedicated to memory, it takes on a new purpose:

The POSTER becomes part of the archive.

Part of the testimony.

Part of the inheritance.

It doesn’t advertise.

It preserves.

✧ POSTER Context: Sofubi, Diaspora & the Urban Battlefield

The image doesn’t just sell a Show.

It compresses seventy years of history into one frame.

Postwar Japan turned nuclear trauma into monsters:

Godzilla as radioactive ghost of the bomb.

Ultraman and his kaiju as weekly rituals of survival on TV.

Those creatures were first rubber suits on sound stages,

“giant vinyl Toys in motion.”

Soon they became exactly that: soft vinyl figures—sofubi—

cheap, light, unbreakable dreams for a generation of children.

Some of those dreams crossed the Pacific.

In the ’60s and ’70s, kaiju Toys and hero figures showed up

mostly in Asian corners of Hawai‘i and California.

For many Asian American kids, they were the first time

they saw super-powered faces that looked like theirs.

Not sidekicks.

Not punchlines.

Heroes.

So when Nagata receives that childhood box from Japan,

it’s not “just” a parcel.

It’s a care package of representation.

Proof that another Story exists for him,

and it arrives in sofubi form.

McCarty’s photograph honors that path.

The ArT Toys stand on real concrete.

Background structures hint at industry, infrastructure, aftermath.

The battlefield isn’t a fantasy wasteland;

it’s Los Angeles: the everyday terrain of the Japanese American diaspora.

Drazoran’s body erupts in toxic rainbow: greens, oranges, metallic flashes.

A living fossil of atomic-age anxiety and psychedelic imagination.

Captain Maxx is all discipline and clarity:

red, blue, yellow: primary colors, primary purpose.

Chaos versus structure.

Past versus present.

Inherited fear versus chosen resilience.

And all of it is cast in sofubi:

a “humble” postwar material, once dismissed as cheap Toy vinyl,

now standing on museum Posters as a carrier of cultural memory.

The medium itself is biography.

Soft. Resilient. Molded, remolded, never quite destroyed.

✧ Energy Behind the POSTER: The Pulse Driving the Myth

What is the emotional voltage of this POSTER ?

Identity

Two figures stand side by side, but they also stand as two halves of a person.

Hero and monster.

Assimilation and otherness.

California and Japan.

Nagata’s inner landscape printed at museum scale.

Nostalgia

Sunlight on sofubi evokes childhood floors.

Plastic on concrete.

Play as refuge.

But nostalgia here isn’t soft.

It’s structural.

It’s the skeleton of Nagata’s identity.

Rebellion

The POSTER rebels quietly.

By placing ArT Toy objects often dismissed as trivial, on the pedestal of heroic monumentality.

It whispers:

“If You ignore Play, You ignore the truth.”

Atmosphere

Warm. Clear. A bit uncanny.

As if childhood suddenly stepped into the real world

and asked to be acknowledged.

Legacy

This POSTER doesn’t look forward.

It looks backward to look forward.

It anchors Nagata’s future in his past.

And it tells every collector:

Your shelf isn’t decoration.

It’s biography.

Biography in brief: from collector to creator

Mark Nagata’s journey doesn’t divide into neat chapters. It flows.

He grew up in California, surrounded by comics, Disneyland, Japanese TV. Then came the box: a shipment from relatives overseas. Inside: kaiju toys, vivid and strange. To most, they were playthings. To Nagata, they were proof: You belong to another Story too.

That spark carried forward. He became a freelance illustrator, painting monsters for Goosebumps, living from imagination for over a decade. In 2001 he co-founded Super7, a magazine that gave scattered sofubi collectors a common language. By 2005 he launched his own brand: Max Toy Company. Out came Eyezon, Drazoran, Captain Maxx…characters born not from market studies, but from the lifelong conversation between a collector and his shelves.

At JANM, that continuity was on display. From rows of vintage toys to paintings and original sofubi, all of it formed one sentence: collecting as Memory, Creation as reply

✧ Genealogy of the Movement

Nagata’s story doesn’t float alone.

It sits on a long production line of culture,

stretching from postwar Japan to Hong Kong to California.

When costs rose in Japan,

toy manufacturing moved to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea.

Factories shifted, but the language of vinyl stayed.

In Japan, hobbyists began customizing resin kits in the late ’70s:

limited runs, garage kits, underground fairs.

The idea that a “Toy” could be an artist’s edition

was born quietly in those workshops.

In the late ’90s, Hong Kong artists like Michael Lau

pushed it further…

turning soldier bodies into hip-hop avatars,

street fashion into limited figures,

laying the visual groundwork for what we now call the ArT Toy Movement.

Nagata stands at the confluence of those currents:

Japanese sofubi mythology.

Hong Kong’s street-driven customization ethic.

American diaspora identity.

Max Toy Co. is where all of that becomes personal:

a brand that treats vinyl not as product,

but as a medium for editing Memory.

Exclusives and live moments

The Show didn’t stop at vitrines.

It pulsed with live moments and object rituals.

The JANM Store became an extension of the Exhibition:

Toy Karma book, McCarty’s POSTER print, and limited sofubi:

Mini Eyezon, Mini Drazoran, and an exclusive red Sofubi-Man.

Visitors didn’t just look;

they carried fragments of the Story home.

And then there were drops that blurred history with homage. The Man of Many Weapons sofubi, sculpted in the likeness of martial arts legend Gerald Okamura, was unveiled with a talk and signing. A museum turned into micro ToyCon. An archive turned into a stage.

Why it mattered (and still does)

For Nagata—a Sansei—those Toys were not plastic. They were roots. The Exhibition showed how a child’s playthings can become a map back to heritage.

And the resonance was global. Families from Mexico recalled Ultraman. Visitors from Italy remembered Space Giants. Fans from Hawai‘i saw Kikaida once more. Pop became a passport.

Critics noted the color, the multimedia punch, the overflow of Memory, even when the gallery flow faltered. It drew new people into the Movement. It proved that ArT Toy Exhibitions can live both as cultural ritual and as fandom pulse.

Nagata’s life reminds us: to collect is never passive. It is to edit Memory with your hands.

Final Thought — from Art Toy Gama

You are not “just” a collector.

You are an editor of Memory.

Every ArT Toy You choose is a sentence in Your Story.

Nagata shows us the path many feel but rarely name:

First, You collect because something in the object recognizes You.

Then, You create because the collection begins to speak back.

Finally, You Dis(Play) : because Memory only survives when it’s visible.

That’s why this POSTER matters. Why this Exhibition matters. Why this Movement matters.

At Art Toy Gama we say it clearly: Dis(Play) is the New Memory.

Collect what connects.

Create what persists.

Exhibit who You are.

Because Trends fade. Legacies don’t.

Apple turns specs into beauty. Nike turns sport into mission. Banksy turns walls into rebellion. Nagata turned vinyl into Identity.

And You? When You place an ArT Toy on Your shelf, You are not filling space. You are editing Your autobiography. You are telling forgetting: Not today.

That is the true Kaiju vs Heroes battle.

Not in Tokyo. Not even in a Museum.

It is fought in Memory.

And You decide who wins.

🎯 Explore the Art Toy Gama Store ...

Join The First and Only Art Toy Newsletter Society in the World here: https://emails.arttoygama.com/l/email-subscription

#1000IconicArTToyExhibitions

We’re currently building an Upcoming Publication that explores and celebrates

the most iconic and influential Art Toy exhibitions around the world.

Each article in this series helps document, reflect, and invite the community

to take part in constructing this cultural archive — one exhibition at a time.

We’ve seen countless exhibitions since then: small and large, modest and monumental.

And we love them all.

No matter where they take place or the resources behind them,

every ArT Toy show adds something to the Movement.

Some will make history, others will make Memory. All of them matter.

This is not just documentation.

This is Dis(Play) in the making.

And You’re part of it.

Art Toy Gama Legacy

#ArTToyGamaLegacy

Art Toys. Paintings. Fine Art Prints. Not what You expect.

Real collectors don't follow trends—they redefine them

POSTER analysis. What the image really says

Look carefully and the message is clear:

Drazoran is not just a monster. He is the echo of that childhood box from Japan, an object heavy with ancestry and fear. Captain Maxx is not just a hero. He is the luminous counterweight, the part of Nagata that insists on resilience.

Blown up to city scale, the ArT Toys rewrite the skyline. Childhood becomes architecture. Identity becomes myth.

The POSTER is not asking You to come inside.

It’s telling You the thesis upfront: an ArT Toy can be the key to who You are.

What the exhibition shows

“Kaiju” translates as strange creature. Postwar film and television turned it into monsters that embodied nuclear trauma. And for every monster came a hero—Ultraman, Kamen Rider, Kikaida—champions of survival.

Nagata’s Exhibition mapped that tension. Vintage sofubi lined the cases. His own creations stood beside them. Illustrations, paintings, Goosebumps covers, even Max Toy exclusives. Pop culture reframed as cultural autobiography.

And this wasn’t a static archive. Visitors could step into a VR tour of Nagata’s studio, watch short films, or even “become” a Kaiju through interactive screens. The distance between museum and fandom collapsed.

We didn’t lose our inner child. We turned it into Art.

You collecting, or just hoarding what the algorithm spoon-feeds you?

contact

© 2025. All rights reserved.